A Special Olympian

In the early 1960s Eunice Kennedy Shriver noticed that many special needs children did not have the support or opportunity to participate in physical activities. This inequality encouraged Shriver to open a summer camp that provided children with intellectual disabilities a place to simply be a child and take part in the physical activities that other children their age enjoyed. This summer camp was the foundation for what is known today as the Special Olympics.

Since then, the Special Olympics has become a venue for more than four million athletes, from over 170 countries around the world with intellectual disabilities to compete in athletic games.

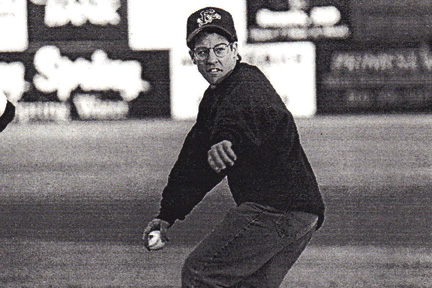

For Zack Reeves, a 41year-old with a developmental disability, the Special Olympics has also become a catalyst for physical competition and has given him the strength to not just compete, but also to win.

Zack Reeves is the son of Dr. Marie Reeves, quality assurance specialist at the U.S. Army Medical Materiel Development Activity at Fort Detrick, Md.

Dr. Reeves said Zack began competing in the Special Olympics, due to "Zack's brother, who is three years older and was a very good athlete," said Dr. Reeves. "[Zack] was always athletic from being dragged to things by his brother."

Zack has been competing in the Special Olympics since he was 15 years old, beginning in Charlottesville, Va. With over 32 sports offered for competition by the Special Olympics, Zack competes in several events throughout the year including softball, bowling, weight lifting, and alpine skiing.

If you ask Zack how many medals he has won, you may as well wait for someone to recite the Declaration of Independence, it would take less time. Through the many years of competition, Zack has won over 120 medals in various events. "I have more gold medals than Michael Phelps," said Zack.

Currently, Zack lives with his mother in Frederick, Md. and is preparing for the next competition. The Special Olympics offers year round training and competition, to help promote a sense of empowerment to the disabled community. It is this sense of empowerment that has helped Zack manage two jobs, volunteer work, training, and competing.

"I like Special Olympics because it lets me see how I can get better at bowling, or skiing or softball, every year," said Zack.

He has plans to pursue coaching for the Special Olympics, and to "help my friends in the games."

"His personal goal is to bowl a perfect game, a 300, and keep working at St. John's and Giant. He is very involved with Community Living and the ARC of Frederick County where he both gives and receives support," said Reeves. "Eventually Zack will live in his own home with a care giver to prepare him for life without me."

[Editor's Note:] Thanks to Shriver, Zack and millions of others with intellectual disabilities can compete in an equal atmosphere, where they may forget about their disabilities and focus on what they can personally accomplish. The Special Olympics gives individuals with disabilities a chance to push themselves, and know the joy and pride in winning, as well as the sorrow and pain of defeat. It is these basic emotions that make every human and is a "special" thing to give disabled individuals the sense of normalcy. For over four million athletes with disabilities, the Special Olympics is a place where they are not defined by their disability, but by what they can achieve.